Ataxia is an extremely important clinical sign that has a broad and important differential diagnosis. Causes of ataxia include posterior circulation strokes and various toxic and metabolic insults to the cerebellum (and sometimes to the spinocerebellar tracts).

Ataxia can be a very subtle physical finding, especially when you don’t know what to look for or when you are busy looking for something else! To help you remember what to look for, break down your clinical “search” in a way that reflects the natural evolution of the patient encounter (the bolded stuff is super-important!):

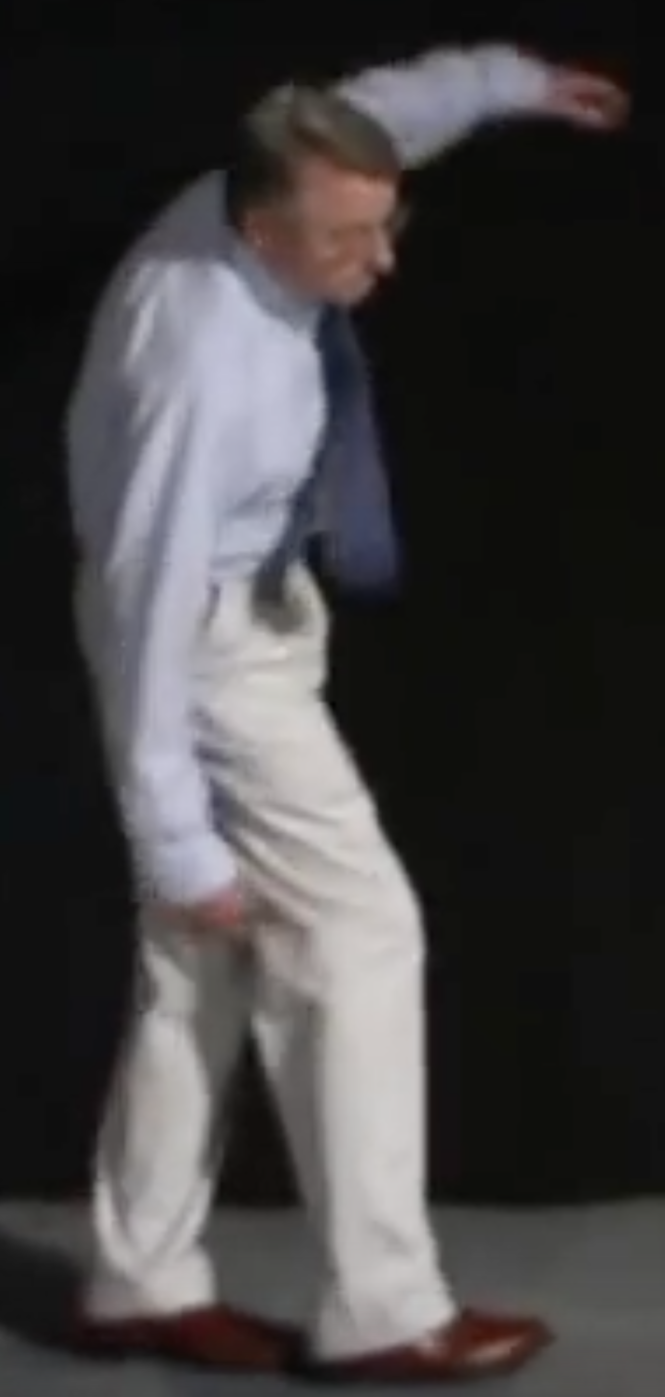

- Gait (patient walks into the room): look for truncal ataxia, a wide-based, staggering gait, as with drunk patients), which may be accentuated with heel-to-toe walking (“tandem gait”). If due to unilateral lesion, patients often veer to the ipsilateral side. Here is one of the best demonstration of an ataxic gait anywhere on the internet!

- Eyes (eye contact is establish): look for nystagmus and titubation (bobbing of the head). It is extremely difficult for patients with ataxia to fix their gaze on you without constant adjustments.

So if your patient can make good eye contact with you for more than a few seconds, chances are they don’t have ataxia. - Speech (introduction and history taking): listen for sudden changes in tempo, volume and pitch. Unlike aphasia, which is a language/comprehension problem, ataxic dysarthria is exclusively a vocal muscles coordination problem. Patients with isolated ataxic dysarthria will have intact comprehension and a preserved vocabulary.

- Limbs (the physical examination):

- Check the finger-to-nose test and look for:

- Delayed initiation of movement.

- Dysmetria (tendency to overshoot or undershoot the target).

- Intention tremor: the tremor, which is present during volitional movements, becomes worse as the patient’s finger gets closer to the target.

- Check for the ability to perform alternating rapid movements: for example, ask patients to rapidly pronate and supinate their hands against their thighs. Or, you can ask the patient to rapidly touch the tip of each finger with the tip of the thumb, in rapid succession. Clumsy, slow and irregular movements are called dysdiadochokinesia, which is a sign of cerebellar ataxia.

- Check the finger-to-nose test and look for:

Leave a Reply